Blood At the Root

North Florida's history of slavery, racism and public lynchings

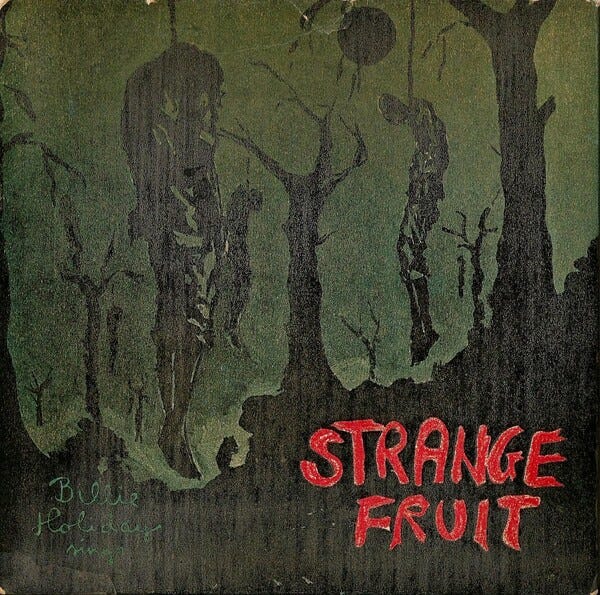

Southern trees bear strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

“Here is fruit for the crows to pluck…”

Jewish-American songwriter Abe Meeropol’s “Strange Fruit” was most famously recorded by Billie Holiday in 1939, while Nina Simone’s chill-inducing 1965 rendition is equally haunting, and even more visceral.

The song was originally written as a poem titled “Bitter Fruit” in 1937, in reaction to and protest against the rampant lynching of Black Americans. Between 1877 and 1950, more than four thousand Black men, women, and children were killed by white mobs. Much of the violence was a direct result of Black men being accused of physically and/or sexually assaulting white women. It’s a familiar trope, as protecting and defending the supposed purity and honor of white women has long been used as motivation and justification for anti-Black hate crimes.

While it is to be expected that most lynchings occurred in the Deep South, it may surprise some that during this period, it was Florida (with 311 lynchings) that saw more per capita than any other Southern state.

Part I: Background

The land of red clay and Black gold

The boundaries of North Florida depend on who you ask, but it’s generally considered to stretch from Escambia County on the far northwest end to Marion County, in the lower northeastern part of the state. While many don’t consider Florida to be the true South, it very much is, down to its 1845 establishment as a slave state. The Southern pedigree is strongest in the Panhandle—my neck of the woods—which is close to Alabama and Georgia geographically as well as culturally.

Before the Civil War, North Florida’s fertile soil attracted opportunistic cotton and tobacco farmers from Georgia, the Carolinas, Maryland, and Virginia, who developed the area into what is sometimes referred to as the plantation belt. Many of those "stately mansions" still exist today. Some became quail and turkey hunting properties, though they often kept the “plantation” in their names. Others have been whitewashed into wedding venues, B&Bs or something equally disrespectful, while the rest exist in various stages of decay, like crumbling, ivy-covered Southern Gothic set pieces.

In addition, the majority of the region’s counties bear the names of assorted white supremacists, slave owners and Confederate sympathizers: Baker, Bradford, Calhoun, Clay, Duval, Gadsden, Jackson, Jefferson, Levy, Madison, Marion, Taylor, and Washington.

Tallahassee, the 200-year-old capital, was the only state capital east of the Mississippi River not taken by the Union Army. It is the seat of Leon County, which was once the epicenter of Florida’s slave trade. From the 1820s up to the Civil War, Leon County generated more revenue from forced labor and had a higher percentage of enslaved people than anywhere else in the state. By 1860, they outnumbered whites 3 to 1.

North Florida is a land of contradictions and duality. It does indeed have palm trees, crystal clear turquoise water, and the sugar-white sands of the world’s most beautiful beaches. These features are juxtaposed with an expansive rural landscape that is equally breath-taking, though it is far more tainted, and always carries a hint of foreboding.

One can get lost in the dense pine forests on purpose or they can swallow you whole against your will. The endless unpaved back roads can be peaceful or they can be desolate, depending on how you ended up there. These same back roads, for many, have only led one way.

They run next to bottomless blackwater swamps, whose depths hold the figurative and literal skeletons of the past. Black blood has long been spilled in this red clay, and the branches of our sprawling Southern live oaks have often been heavy with more than their share of strange fruit.

In the paragraphs below, I highlight several lynchings and race riots which took place in North Florida, from the turn of the 20th century to the mid-1940s, such as the barbaric murder of Claude Neal and the notorious Rosewood massacre. While some incidents are more widely-known than others, the common theme is that none of the perpetrators were ever held responsible, including those cases which led to FBI investigations.

NOTE: Further information can be found in the in-text citations, especially in the work of Tameka Bradley Hobbs, Dr. Patricia Hilliard-Nunn, and the Equal Justice Initiative. Historical newspapers and digital collections like the Florida State Library and Archives are also valuable resources.

Part II: Massacres and mob violence

Incidents, by county

Escambia County (5 lynchings between 1877-1950)

Leander Shaw, 1908 - Pensacola

Shaw was accused of the rape and murder of Lillie Davis, a white woman. On July 29th, she had been found in her home with head injuries and a slit throat. Two hours later, Shaw was apprehended near Bayou Texar, allegedly washing a bloody shirt and in possession of a bloody knife and Colt revolver. He was taken to the hospital, where Davis identified him as her attacker. She would die three days later.

Shaw was then transported to the Escambia County Jail, where Sheriff James C. Van Pelt tried and failed to disperse the gathering mob. After the crowd broke the jail yard gate, Van Pelt and his men opened fire and and a shootout ensued. While the deputies were engaged, another group scaled the back wall of the jail overtook the men guarding Shaw. Attaching a noose around his neck, they dragged Shaw through the streets and hung him from a lamp post in Plaza Ferdinand VII. Afterwards, his body was riddled with roughly 500 bullets.

Jackson County (9 lynchings between 1877-1950)

Claude Neal, 1934

The murder of Claude Neal is one of the most heinous lynchings to occur in the United States. Its sheer savagery is indicative of the historical dehumanization of Black people and disregard (and disdain) for Black lives.

Neal was a 23-year-old farmhand from rural Jackson County, Florida. In 1934, he was accused of raping and murdering Lola Cannady, a white woman, though evidence of his guilt was circumstantial at best. Neal also reportedly confessed to the crime during police questioning, first implicating himself and another man, then claiming that he acted alone. Considering the social conditions of the time, the confession was likely given under physical duress.

Neal was moved around to several jails in the Panhandle to avoid mob violence, eventually being sent to the Escambia County (Ala.) Jail in Brewton, Alabama. Despite this, he was kidnapped on October 26, 1934, and taken to a secluded area on the Chattahoochee River, near Greenville, Florida. There, Neal was tortured for hours, and his body horrifically mutilated, before he was finally killed and dragged behind a vehicle to the Cannady family farm.

After being subjected to further indignities by a crowd of roughly two thousand, Neal’s body was driven to the Jackson County Courthouse in Marianna and hung from a tree. Photographers sold postcards of his disfigured corpse for 50 cents each, while some spectators reportedly kept his fingers and toes as souvenirs.

Sheriff Flake Chambliss cut Neal down the following morning, and a smaller mob demanded that he be hung back up. When Chambliss refused, they retaliated by attacking and injuring around 200 Black residents, burning and looting their homes in the process. The National Guard was eventually called in to restore order.

Cellos Harrison, 1943 - Marianna

Less than a decade after Neal’s murder, Jackson County was once again the site of unchecked white mob violence. Farm worker Cellos Harrison was found guilty and sentenced to death twice for killing white gas station attendant Johnnie Mayo in 1940. Both times the verdict was rendered by all-white juries and both times the Florida Supreme Court threw out the conviction upon appeal.

Though the court also ruled that Harrison could not be retried for the crime, he charged again five days after his release and held in the Jackson County Jail. On June 15, 1943, he was taken from the jail by a small group of masked men and beaten to death. His body was found just outside of Marianna.

Leon County (4 lynchings between 1877-1950)

Pierce Taylor, 1897 - Tallahassee

Taylor was being held in the Leon County Jail, accused of attempting to rape a young white woman after she refused him a ride on her wagon. On the night of January 23, 1897, a group of masked white men abducted Taylor from his cell and hung him from an oak tree in yard. The rabid mob repeatedly shot him as he dangled from the rope, though it is unclear if Taylor was still alive at that point.

Mick Morris, 1909 - Tallahassee

Morris was a turpentine worker accused of fatally shooting Leon County Sheriff Willie Langston while the latter was attempting to serve a warrant on him. After the shooting, Morris fled to his father-in-law’s home in nearby Thomasville, Georgia, where he was later apprehended. Morris reportedly claimed the shooting was accidental and subsequently plead guilty in hopes of avoiding the death penalty. Despite this, he was sentenced to the gallows after a dubious trial that lasted less than one day. On June 6, 1909, Morris was taken from his cell by 15 masked men, beat with a club, and hung from a nearby tree.

Richard Hawkins and Ernest Ponder, 1937 - Tallahassee

On July 18, 1937, two men broke into a local business, where they were interrupted and arrested by Officer J.V. Kelley. When Kelley attempted to transport the two men, one stabbed him in the mouth before they fled. Within the hour, Hawkins and Ponder, both 18, were taken into custody. There are no police or newspaper reports that explain exactly how law enforcement apprehended them so quickly or confirmed that they were even the right suspects.

The two teenagers were later kidnapped from Leon County Jail and driven outside the city limits, where they were murdered. Their bodies were riddled with bullets and they were left to bleed out on the side of the road. As they lay dying, their murderers put up signs warning other Black people that they would suffer the same fate if they ever dared to step out of their place or “harm” a white person.

Gadsden County (4 lynchings between 1877-1950)

A.C. Williams, 1941 - Quincy

On the night of May 11, 1941, William Bell alleged that somebody had burglarized his home and attempted to assaulted his 12-year-old daughter. Shortly before, deputy sheriff Dan Davis had pursued A.C. Williams in the area after responding to the sound of gunshots, apprehending him in a nearby residence. Williams was taken into custody after he was allegedly found in possession of a knife, in addition to a pocket watch, and a wrist watch that Davis did not believe belonged to him. After hearing Bell’s story, authorities officially charged Williams for the burglary and attempted assault. Later court testimony by Thelma Bell and her parents proved to be both improbable and inconsistent.

As he was making his rounds on foot in the early morning hours of May 12, Davis was forced into a vehicle by a group of masked men, taken to the jailhouse, and made to disclose the location of Williams’ cell. Williams survived after being beaten, shot, and left for dead, and made his way back to his mother’s house. There, law enforcement arranged for him to be taken to Florida Agricultural & Mechanical College Hospital, the only facility in the area that treated Black patients. Williams, being transported by hearse, was kidnapped a second time and shot to death. His body was found the next day on a bridge north of Quincy.

Columbia County (21 lynchings between 1877-1950)

Lake City mass lynching, 1911 - Lake City

A Black turpentine worker by the name of Norris and five of his unnamed associates were booked into the Columbia County Jail for killing one white man and wounding another. Norris had gotten into an altercation with a co-worker, who later came to his house with several other men to continue the confrontation. A shootout ensued, after which the six men waited for the police and surrendered.

Shortly afterward, a group of men posing as law enforcement gained entry to the jail using a forged telegram. They removed Norris and the others from the jail under the pretense of moving them to Jacksonville to avoid a mob forming in Tallahassee. In reality, they were taken to the outskirts of town and shot multiple times.

Duval County (7 lynchings between 1877-1950)

Bowman Cook & John Morine, 1919 - Jacksonville

During the Red Summer of 1919, several Black taxi drivers in Jacksonville were murdered by white passengers. After police refused to investigate, many began refusing to pick up white people. In August, George Dubose, who was upset about being denied service, fired into a crowd of Black people and killed one person. Bowman Cook and John Morine, both WWI veterans, were accused without evidence of killing Dubose (who happened to be the brother of the justice of the peace) in retaliation.

On the night of August 24, 1919, a mob arrived at the Duval County Jail, in search of another Black inmate, Ed Jones. Jones, who had been accused of assaulting a white girl, had already been moved for his protection. The group instead took Cook and Morine to the gates of Evergreen Cemetery and shot them to death. Cook’s body was left in a ditch, while Morine’s was dragged behind a vehicle for 50 blocks before being dumped in Hemming Park.

Alachua County (19 lynchings between 1877-1950)

Jumbo Clark, 1904 - High Springs

Clark was accused of the alleged assault of a 14-year-old white girl. After his arrest, he was made to confront the girl, who reportedly identified him as her attacker. As Clark was being transported to Gainesville, he was intercepted and abducted by a group of roughly 50 men, before being hanged from an oak tree.

Newberry Six, 1916 - Newberry

On August 17, 1916, Alachua County constable George Wynne attempted to serve a warrant on Boisey Long for stealing hogs. A conflict ensued in which Long allegedly fatally shot Wynne and wounded his associate, L.G Harris. Narratives differ on who fired the first shot. Long initially escaped, but turned himself in two days later.

In the meantime, a posse murdered James Dennis, whom they suspected of hiding Long. Gilbert and Mary Dennis (who was pregnant), Long’s wife Stella Long, Andrew McHenry and Rev. Joshua Baskin were accused of helping Long get away and taken into custody. After being arrested, they were taken from the jailhouse by a mob and hanged. Boisey Long was convicted of the murder and hanged on October 16.

Henry White, 1913 - Campville

On December 13, 1913, White was abducted from a train station by a white lynch mob and hanged from a tree. He had allegedly been found underneath the bed of a white woman.

Lafayette County (11 lynchings between 1877-1950)

Charles Strong, 1922 - Mayo

In January of 1922, white mailman W.R. Taylor was killed inside the home of Charles Strong. Taylor had entered the residence while investigating an alleged domestic disturbance and was killed by a shotgun blast. Strong maintained that he was not responsible for the man’s death and went on the run. He was apprehended by law enforcement three days later. On the way to the jailhouse, they were met by a white mob of roughly 1,000, who abducted Strong before hanging him from a tree on the outskirts of town. Per their historical disrespect and desecration of Black bodies, the mob then riddled his dead body with bullets.

Taylor County (14 lynchings between 1877-1950)

Perry Massacre, 1922 - Perry

On December 2, 1922, the body of Annie “Ruby” Hendry was found in Perry. Her throat had been slashed and she had been beaten beyond recognition. A shotgun and straight razor found at the scene were allegedly linked to Charles Wright, an escaped convict from neighboring Dixie County.

In the following days, Cubrit Dixon and three more unidentified Black men were killed by deputized white mobs. Black schools, homes, and buildings were also burned down. Arthur Young, an alleged accomplice and Wright were captured on December 7 and 8, respectively. Wright was taken from police custody and burned alive, after which the crowd kept pieces of his body and clothing as souvenirs. On December 12, another lynch mob abducted Young as he was being moved from the Taylor County Jail, before shooting him to death and hanging him from a tree next to the highway.

Levy County (8 lynchings between 1877-1950)

Rosewood massacre, 1923 - Rosewood

The Rosewood massacre is arguably the most well-known instance of racial violence in Florida, if not the U.S. Mostly unheard of outside of the area until the 1980s, the incident came into the public consciousness due to investigative reporting and John Singleton’s 1997 film of the same name. During the first week of January 1923, the majority-Black town, was completely destroyed by a white woman’s lie. Fannie Taylor claimed to have been assaulted by a Black man, though her assailant was most likely the white man with whom she had been having an affair.

All Black-owned buildings were burned to the ground by bloodthirsty white mobs and Black residents were shot on sight. Two whites were killed during a shootout at the Carrier house. Many of those who escaped either hid in the nearby swamps or took refuge with local whites. Two wealthy white brothers arranged a train to transport many of the surviving women and children to Gainesville, though fear of lynch mobs resulted in their refusal to take on Black men. The official Black death toll is six: James Carrier, Lexie Gordon, Mingo Williams, Sam Carter, Sarah Carrier, and Sylvester Carrier, though survivors have asserted closer to 30. Others report seeing mass graves which imply far more casualties.

You can also read more about Rosewood in my write-up on the Crossroads Collective Ko-fi page: The Rosewood Massacre

Suwanee County, FL (13 lynchings between 1877-1950)

Willie James Howard, 1944 - Live Oak

By the 1940s, lynchings had begun to decline nationwide, though they had not ceased. On January 2, 1944, fifteen-year-old Willie James Howard drowned in the Suwannee River after sending a Christmas card. While Willie James sent cards to all his coworkers at the Van Priest Dime Store, the allegedly flirtatious one he sent to a young white girl named Cynthia Goff was a grievous violation of one of the Jim Crow South’s cardinal social rules.

Phil Goff, Cynthia’s father, who either discovered or was shown the letter, went to the Howard home in Live Oak, accompanied by two other men. They dragged the teenager away from his mother, Lula, at gunpoint, before driving to his father James’s job and abducting him. Goff and his accomplices took Willie James and James to an embankment above the Suwanee River, where they bound the boy’s hands and feet. Walking the younger Howard to edge, they told him to choose between being shot and drowning in the cold water below.

James Howard was forced to watch at gunpoint as his son dropped into the river, where his body was found the next day. Goff later claimed they had only taken the two so that James could beat his son to teach him a lesson about writing letters to white girls, but that the boy declared that he would die first, before jumping in the river. Goff claimed that James had done nothing to attempt to save his child. After the drowning, James was forced to sign an affidavit at the police station which corroborated Goff’s account.

James and Lula Howard sold their home and fled Live Oak within days, only revealing the truth about their son’s forced drowning once they were safely in Orlando.

Madison County (16 lynchings between 1877-1950)

Bucky Young, 1936

Young was a yardman and handyman in Greenville, Florida. He was murdered by a lynch mob after being accused of attacking the white woman who had hired him to paint. Young was arrested, but released, before being abducted from his home. He was shot and left for dead, but managed to crawl to the home of a white man who took him to Greenville. There, he was placed in jail and treated by a local doctor. Young had yet to be charged, so he was released and allowed to return home. He was taken from his home again, and killed by a group of men on the outskirts of town. The local coroner refused to perform an autopsy.

Jesse James Payne, 1945 - Greenville

Greenville, Florida, holds the dubious honor of being the location of the nation’s only recorded lynching in 1945. Sharecropper Jesse James Payne was kidnapped at gunpoint after a money dispute with his boss, Levy Goodman. After being taken to a secluded area, he escaped into the woods. Goodman then raised a posse and changed his story, falsely accusing Payne of sexually abusing his five-year-old daughter. Attorney General J. Tom Watson, an open white supremacist, support this narrative. He lied in public statements, alleging that a medical exam concluded that Goodman’s daughter had been both abused and exposed to a sexually transmitted infection.

Payne was later caught after being shot by a deputy sheriff. He was taken to the Jefferson County Jail in Monticello, from which he was abducted while he awaited trial. The sheriff had left the jail unguarded, despite the obvious threat of mob action, and Payne was taken sometime in the middle of the night. His bullet-riddled body was found on the side of the road the next morning.

Though there are undoubtedly many more, Payne’s murder was the last recorded lynching in North Florida.

While these painful events may be in the past, the racial animus that drove them is not.

August 2023: A white supremacist gunned down three Black people in a Jacksonville Dollar General.

July 2012: Jordan Davis was shot to death over loud music by David Michael Dunn, a white man who “hates that thug music.”

February 2012: Just five months before Davis’s murder, 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was gunned down by George Zimmerman.

All three instances can be considered to be modern-day lynchings. Florida—like the United States—has yet to reckon with its original sin of human bondage.

And those who ignore history, are doomed to repeat it.

And that’s exactly what continues to happen with brown and black people. I am so ashamed of the less than human race.

All of this makes me sick.